About Me

I am just some guy with a cool wife and funny kids who likes making things that probably don’t need to exist, like this website, a bunch of albums, and all these words.

I made Resolution and I just finished an acoustic album.

About Me

I am just some guy with a cool wife and funny kids who likes making things that probably don’t need to exist, like this website, a bunch of albums, and all these words.

Here’s some of my work.

I’m also the lunatic behind a what-if scenario planning & goal setting application called Resolution. You can use it for free here, or check out our fairly large set of examples.

Look at This Hat

I recently finished an acoustic album, and it came out pretty good! If you like stripped down, half-earnest half-winking-at-the-camera punk rock songs recorded by some Dad in his living room, you should listen to it.

Listen Now:

Abolishing Things

I get why people are hesitant to abolish large parts of the government. I also get why, despite this, more and more people want to abolish the Immigration, Customs, and Enforcement (ICE) agency.

While ICE’s recent psychopathic-clown-show tactics have put it under a particularly bright spotlight, ultimately I think people want to “abolish” it for the same reasons some people wanted to “abolish” various local police organizations in 2020. At some point, it starts to feel like the safeguards on positions of state power are entirely voluntary, and that the people with that state-granted power are the ones who get to decide whether to obey them or not. Those aren’t really safeguards! For all the talk of rounding up people who “broke the law”, regular-ass Dads like me have been watching videos of morons in tactical gear blatantly violating a wide variety of rules, laws, and even Constitutional rights with absolutely no consequences whatsoever, let alone appropriate ones.

For instance, I’m sure I have seen over a hundred videos in the last six months of ICE and CBP employees doing something that made me think “that guy should go to prison for that”, or maybe even “I think you’re supposed to go to prison for that”, and none of those guys are going to go to prison for those things, or even lose their jobs. Personally, I don’t think it’s weird for someone, at a certain point, to just say “the hell with all of this” and demand a fundamental rewrite of this part of the social contract.

Immunity as a Given

Many policy debates are essentially an exercise in trying to make people accept certain “givens”. One given that’s been pushed forever is the idea that law enforcement, for the most part, needs to be in charge of regulating itself. If someone from the government with a gun does something that looks or feels illegal, it should basically be up to a bunch of people who have the same job to decide whether there should be any repercussions, and usually the answer is “no”.

Now, you can make an argument for this. You can say a world where law enforcement is held accountable by some other function, and not allowed to be given vast immunity to a host of otherwise criminal actions, would be a world where laws could not be enforced, and everything would go to shit. You can say that if police, or ICE agents, or whomever is zip-tying you today could not operate with absolute confidence that if they get scared, it’s okay for them to shoot whatever they are scared of, that there would functionally be no policing at all. You can argue that! However, I do not find it especially compelling.

What I think is much, much more likely is that most people have done some math in their head that goes something like this. If a policy makes the police 5% more effective at protecting you from things you don’t like, but 5000% more likely to hurt, rob, or kill innocent people while they do so, that seems like a bad trade. BUT, if you think the 5000% increase in abuse will happen exclusively to people who you are not concerned about, that trade seems fine. I mean, it shouldn’t really seem fine, morally, but I would guess that it probably does, in fact, seem pretty fine to a lot of people. But this is just run of the mill “leopards eating faces” stuff. The point isn’t “no real-world accountability breeds bad outcomes for state power”, even though that’s also true. The point is “if you’ve removed all real-world accountability you can’t fix bad outcomes by adjusting the particulars of accountability”.

In this case, that’s the whole “do we fix ICE or get rid of it?” argument, which is a good argument to have. From my perspective, though, it’s also not a very complicated one. ICE — and unfortunately, most 21st century law enforcement — have insisted on building policy around the idea that law enforcement cannot be held accountable the way regular people are, and in fact need to be fundamentally immune to almost all of the consequences a normal person would face for doing various violent or grossly illegal things to another normal person. That’s non-negotiable, apparently. And now, with that principle in place, let’s make some rules!

See why this is a waste of time? There are already lots of rules! They’re simply being ignored because they can be ignored, and the only answer we can come up with are more rules that will also be ignored, because underneath it all too many of us still think law enforcement should get to decide if it did something bad or not.

In my heart of hearts, I think this is what animates people who want to abolish various law enforcement functions. I don’t actually think — in most cases — it’s some hippy-dippy belief that crime doesn’t exist (although it really would help if the police solved more crimes) or that there is no need for law enforcement of any sort. Instead, it’s a rejection of the idea that these organizations should exist as so many of them do — self-regulated, armed, well-funded, unionized, highly political groups that receive massive judicial and legislative deference in almost every scenario.

I think a world where turning off your legally-required body camera, for instance, and then arresting someone, was potentially a form of criminal negligence is absolutely unthinkable to a lot of people. But I think that position understates the seriousness of the task given to armed agents of the state. I didn’t invent it, but I think the idea of “higher standards + real accountability + much higher salaries” isn’t crazy even though it’s not a panacea and the devil’s in the details. Law enforcement is hard, but so is nuclear physics — and we don’t let nuclear power plants self-regulate or operate with the knowledge that everyone working there will be immune from almost any criminal charge if they decide to kill a bunch of people.

And those are real cops! ICE makes the disconnect here even more obvious. What utility are we even getting out of these goons? I’m not going to stand around and listen to a theoretical argument about utility ICE might have if the people who work for it did their job in a completely different manner than the way — given carte blanche to do whatever they want and total deference from local authorities — they choose to actually do it. I’m going to take it as it is. They don’t follow rules. They lie constantly. They willfully commit sociopathic violence with no consequences. Logically, how would you even fix that? Find some magic politician who will be our benevolent dictator and use his unaccountable army thoughtfully?

We had versions of that for a long time. No, not an actually benevolent ICE (imagine that, lol), but one that put at least some limits on itself because the idea of just telling the public, in every… single… interaction, to eat shit and die seemed… unseemly. But it was only a matter of time before thugs and goons would be drawn to the warm flame of unaccountable, masked violence and bullying, and now ICE simply is what it is — a relationship defined by its lack of boundaries, which means we can’t fix it with boundaries. It just has to go, and then we try again with something completely different.

Actually, Hacks are Bad

If I may — a “hack” is not a good thing. At their best, hacks are clever, temporary exploits that get you where you need for the time being, or if you’re a criminal, a way to bypass security that (by definition) you aren’t supposed to be bypassing. Most hacks are just crappy, lazy, unrealistic implementations that obscure cost, sometimes deferring it but also usually increasing it in the process. The worst ones are literally scams.

Don’t aspire to come up with hacks. There are way too many hacks already. Aspire to come up with real, thoughtful solutions, and advocate for the time and resources to execute them.

Rage as a Service

Trolling people is easier than being funny or clever. This is not a new challenge, but here we are, once again pretending that failing at it is a tactic and not a weakness.

“Some advertising and marketing agencies are now intentionally leaning into the volatility of the current political climate, not to take a stand but to manufacture outrage,” said Mikah Sellers, an advertising consultant who has worked with major brands including Booz Allen Hamilton and Carfax. Companies are tapping into cultural rifts and driving wedges in hopes of capitalizing on the strife, he said.

How will they capitalize on pissing people off? Unclear! In fact, here are the companies (sometimes a generous classification) referenced in this article that are allegedly getting exactly what they want from this tactic:

- Friend

- Nucleus Genomics

- Skims (Kim Kardashian’s clothing brand)

- Sabrina Carpenter

- Pippa

- Cluely

- Clad Labs

- Artisan

Leave the pop musician and the reality star aside, because I understand the commercial viability of trolling in those industries. But the rest? These companies are not successful. They can scream all they’d like about how they’re getting what they want as they slowly (or quickly) go out of business, but this largely startup-fueled delusion that life is either TikTok or the Trump administration, and you basically need attract eyeballs at any cost and then go from there is not actually backed up by the facts or financials.

And the thing is, the smart counter to bland, play-it-safe branding isn’t stupid, insecure edge-lording. It’s staring you right in the face — it’s CostCo, dammit! If you want to be edgy, get your name in a story like this, which has spread around the internet organically so much on its own that it has its own Snopes article confirming its authenticity:

“I came to (Jim Sinegal) once and I said, ‘Jim, we can’t sell this hot dog for a buck fifty. We are losing our rear ends.’ And he said, ‘If you raise the effing hot dog, I will kill you. Figure it out.”

Just an incredible quote. No notes. This is the kind of shit people want. That they feel. It’s not generation or culture-coded, other than the fact that people are constantly being screwed by companies acting in their rational, best financial interests at our expense, and here’s a guy running a company who is just MAD about it, stomping on everyone’s least favorite title (“CEO”) and even threatening (tongue-in-cheek) violence over it!

None of this is new. How about this Dollar Shave Club launch ad, from over a decade ago?

It’s the same thing. It works because (1) it’s violently pro-customer, and (2) it’s about what the company actually does to/for those customers. The edgy tone is fine, but the cause of that edginess feels more like genuine excitement about what they’re able to do for customers, and anger at the worst, most anti-customer aspects of their competitors.

When everyone was watching this ad and talking about how they needed one just like it, we didn’t have to figure out what percentage of them were hate-watching it, because it was zero. In fact, when everyone tried to do this, the problem they ran into was (a) they weren’t actually this passionate about their business or, more specifically, their differentiator, and (b) they’re not fun, creative, or funny!

Conversely, this latest run of pathetically click baiting people into looking at you for a second, rolling their eyes, and then, as they walk away, shouting “Ha! You’re in the funnel now!” completely misses the point. It fees like it comes from a generation of attention-grabbers who have spent too much of their lives on phones, in feeds, and quantifying every aspect of their social experiences. And while generational preferences adjust (I’m sure much of their audience is afflicted by this same problem), we’re not talking about music and language choices here. We’re talking about whether people want to feel happy or angry, like a great new day is dawning or the dumbest, most obviously wrong person in the world just slid into their DMs.

Nobody wants that. My kids don’t want to feel that way, and neither do their friends. When they do feel that way, sure, it’s hard to escape. But they hate it, and banking on people who hate you and what you represent to become customers (let alone repeat customers) is insane.

Accountablli-Buddy

My Theory of Productivity

Allow me a theory. I probably didn’t invent this, but if I did, bully for me.

Work output, when increased beyond the amount of available accountability, without a matching increase the available accountability, will never generate a lasting increase in productivity.

Here’s what I mean by all these terms. Work output is the amount of stuff you make or things you get done. Maybe you make toys, maybe you insure businesses against floods, maybe you send emails. Work output is necessary but not sufficient to generate productivity, which is often why doing actual, productive work is challenging. If all you needed was raw work output, you could just jam out whatever all day as quickly and easily as possible and solve lots of problems. Nothing works this way.

This is why we have accountability. Accountability, in my parlance, is sort of a backstop against work output. It doesn’t necessarily guarantee that all work output is good (that would be “micromanagement”, which is a great way to drive work output to zero), but it ensures that for every kind of bad output, there is time, energy, and brainpower available to figure out why that’s happening and take on the responsibility of preventing it. In other words, mistakes are okay, but just making the same ones over and over again at similar (or increasing) rates is not.

Productivity is when these two things align. If work output goes up, and a person, system, or process is available to make sure that work output is positive (or at least not negative), you will almost always see a commensurate improvement in productivity. I define that as whatever positive outcome your organization is trying to accomplish (usually whatever gets us paid — the insuring, the toys, the emails, etc.)

Accountability as a Limiting Factor

As we are frequently reminded by people trying to get us to invest in insane exciting things, the world has gone through many productivity revolutions thanks to various technological innovations. While some of things improved the quality of things, or the safety of the people making them, the most obvious impact of the biggest ones is a large, comparatively inexpensive increase in work output. My new factory can make a thousand pairs of pants in the time it used to make a hundred, resulting in both cheaper pants and higher margins for me. Everyone wins. My new corn can grow on land that used to be barren, and using water from far away brought in by pumps that didn’t exist before. More corn, less useless land, everyone wins, at least until I start growing fake, inedible corn to take advantage of massive agricultural subsidies.

I am a huge fan of these developments in general, and always have been, even though I am not an industrialist but merely a simple 21st century office drone. I am constantly seeking ways for technology to improve my work output, because when I succeed at this, I usually receive praise (and occasionally promotions!) for actually doing less work. It’s fantastic, and if you’ll allow me, just very American in the best way.

(music swells)

But there’s a catch. I mean, it’s not really a catch so much as a limiting factor. My technological innovation can’t increase my work output beyond my ability to make sure my work output isn’t actively harmful. Have you ever sent out an automated email to a large customer base that said “Hi, {FIRST NAME}”? Obviously I haven’t, I am totally asking for a friend. But that’s an example of the risk of increasing work output beyond accountability bandwidth.

Now, in the case of the embarrassing auto-email, we make that tradeoff 10 times out of 10, but there’s still accountability. Just ask… my friend! When you send that stupid email, you’re going to hear about it. Recipients will respond and yell at you, co-workers will forward angry customer replies, and eventually you’re going to hear about it from your boss. If they are a bad boss, they will tell you this is unacceptable and maybe call you an idiot and then walk away and start working on your Performance Improvement Plan so they can fire you. If they are a good boss, they will help you figure out some way to audit the “Name” information in the CRM, or use “no data fallback” feature in your email designer. But either way, these emails will not just blast out with FIRST NAME on them forever. And that, my friends… is accountability.

Innovations that increase work output must, by the rules of my theory, be paired with innovations in accountability, or else that automation will not generate productivity.

By and large, this is exactly what has happened with most work output-increasing technological innovations, otherwise they would never have stuck around. Various technologies have improved our ability to review things, reduce random errors, and more quickly and easily work with various problem solving experts in the event that something goes wrong. These are good things, even though they are less sexy than, you know, the cotton gin or the assembly line or whatever. Hell, unions are an accountability innovation in a lot of ways; an organizational check on the staggering increase in work output (and some of the resulting bad effects) resulting from the Industrial Revolution.

First Salads, Then Robots

Okay, so as legally required by Internet Rules of 2025, let’s now apply this to artificial intelligence, or more accurately, large language models, image generators, and maybe (if you squint) “agents”. There is a funny little dance going on when we talk about these things, because we can’t quite decide if they are supposed to replace us, or be used by us. In general, I find that the conversation — whether about society in general or in a sales pitch for some AI tool — tends to start with replacing, only to then inevitably downshift to “it’s a just a tool/massive force multiplier/etc.” as details and reality begin to weigh down the conversation. The tech industry has been able to dodge a lot of difficult logical questions by flipping this bit back and forth as it suits them.

“Layoffs in the streets, force multiplier in the sheets”, if you will.

But here’s the thing — it actually doesn’t matter because accountability is the limiting factor in either case. Think of it this way. You’d never hire someone with zero accountability. Maybe their accountability is generous, or forgiving (maybe they’re a cousin, I don’t know, I’m from Rhode Island), but unless you’re talking about a legitimate charity case, there’s gotta be some. Even something as simple as saying “if you screw up badly enough, you’ll get fired and then the paychecks will stop” (again, optional in Rhode Island) is a form of accountability, however crude.

So there’s at least an element of accountability in every function, or it’s simply not a productive job, because if there’s no accountability, you’re effectively saying the output doesn’t matter. And that means the accountability bandwidth thing comes into play with every function as well. Somebody was responsible for every caesar salad I made in the summer of 2001 at 22 Bowen’s Bar & Grill. Mostly it was me, but it was also my boss. That doesn’t mean I couldn’t make a mistake on any given salad (oh Lord did I make those), just that you could take any one of those mistakes and say “who is dealing with this by either fixing the cause of this or leaving the organization?” and there’d be an answer every single time. But the system we had in place was predicated on three college kids making every salad to order, by hand. There were only so many we could make, and thus there was a hard cap on both our possible work output and the accountability needed to ensure the value/utility of our output. In short, three college kids who didn’t want to get yelled at or fired in the middle of the summer, plus a full time assistant chef who really didn’t want to get fired, together, could handle the task.

If for some reason the restaurant exploded in popularity and we needed ten guys making salads at once like a Chopt in Midtown, or if the three of us got magic AI salad machines that let us spit out hundreds or thousands of salads a minute, this system would need to evolve for us to use it. Either those machines would need iron-clad safeguards in them (making them effectively error-proof), or you’d need a massive investment in quality control to hold yourself accountable for making good, edible salads. You wouldn’t just 10x the process and say “look how productive we’re being” without anything in place to make sure people weren’t just getting dirty bowls hastily filled with handfuls of chick peas.

Okay, Now Robots

The fundamental business promise of generative AI has a giant, accountability sized hole in it. So far, many vendors have dodged this by making accountability sound like ethics, which many companies will discard for a big enough ROI, but this is a major misread of how business works. Accountability can be about ethics, but it’s really just about outcomes, and there is no reason to think that businesses are willing to throw away their control over outcomes because generating a lot of arbitrary, uncontrolled outcomes now requires little to no human effort.

Bluntly, if you’re selling a massive increase in work output without some way to also massively increase accountability bandwidth, you’re essentially proposing one (or maybe more) of four possibilities:

1. Workers have plenty of unused accountability bandwidth now, so a huge increase in work output is actually great

This doesn’t sound like 2025 to me. Companies have been finding new and more creative ways to avoid being held accountable for things for decades now, with “innovations” ranging from binding arbitration clauses, to liability shield laws, to shutting down support lines and dumping people into user forums. The accountability that remains is almost entirely related to raw financial performance. Companies have been talking about “doing more with less” for years now; I find it hard to believe people are sitting around checking their work twice for lack of anything else to do.

2. It’s worth it for businesses to pay increase accountability bandwidth to meet the huge increase in cheap work output

Is it, though? Every marketing department has to figure out things like “the right number of campaigns to run” precisely because it’s often not worth the cost of installing sufficient accountability. It wouldn’t be worth the cost of doing thousands of additional hours in post-mortems and data analysis just because you could now afford to spin up those campaigns for zero dollars. Then again if we’re not 100x-ing our output here, what’s the value of this innovation? What I could really use is one automated campaign manager who was just as accountable as my human ones…

3. Accountability bandwidth can be increased with the same types of technologies that increase work output

… but that is not a thing, because computers are not accountable. They don’t care. They don’t need to eat. They don’t need to make their parents proud. They don’t need anything, because they’re not alive, and being alive is a non-negotiable part of giving a shit about anything. You can program rules into software, but rules are not the same thing as giving a shit, which you will immediately realize if you ever have to work with someone who doesn’t give a shit about work, but is sufficiently capable of following rules. In some ways that kind of person is just a slow computer, but more importantly, every computer is just a really, really fast version of that annoying employee. There are lots of ways to get different kinds of people to give a shit about different kinds of things (this process is called “middle management”, ask ChatGPT about it), but there zero ways to make computers give a shit about anything. In fact, one of the reasons software can work/write/execute a decision tree so quickly is that it doesn’t give a shit about literally anything, so nothing slows it down.

4. Accountability is irrelevant if you scale work output enough, or it’s just irrelevant in general

Lastly, despite it being a running joke for — I dunno — a hundred years or so, there’s an increasingly weird, inexplicable interest in the “a thousand monkeys on a thousand typewriters will eventually write the greatest novel ever” approach to work. Maybe it’s because some of the world’s most successful high margin businesses are automated, algorithmic trash dispensers with seemingly no limit to how big they can scale. Maybe it’s because we’ve over-financialized basically everything at this point, and we can’t conceive of any system where “N” has some sort of fundamental limit. Maybe it’s something else! But I’m here to tell you that you can’t scale any work output to the point where nothing matters. Facebook is certainly going to try, but for the rest of us, there are only so many places to show your infinite, dynamic ad variations. So even if the numbers are large, they are still numbers, and they still require some form of boring old accountability for results.

Good Automation is Still Good, Bad Automation is Still Bad

Automation is an incredibly valuable thing, but one of the many downsides of the blind rush to automate anything we can find is that some of the most important skills in making automation decisions seem to be atrophying as we race to lower the marginal cost of arbitrary work output. For instance, my little event management project automates the gathering and tracking of events and their related deadlines. You just give it a website, and it goes and finds all the events, all the deadlines, and organizes everything. I hate doing this, it takes me forever, and I make a lot of mistakes, so in general I like this painless increase in work output.

But there’s obviously an accountability issue here as well that I don’t want to ignore. No one is going to want my application to automatically grab tons of irrelevant events and deadlines and shove them into the system. They won’t even want me to automatically grab events and deadlines that are sort of relevant. They want the right ones and only the right ones and since events are not labeled on the internet as “ones you should care about”, there is no ironclad, computer-powered way to do this with 100% certainty, which pushes accountability to my user. So I actually throttle the process by (a) separating the process of finding events from finding deadlines, and (b) making you confirm which ones you want in each process. I could increase the number of events and deadlines you find, and reduce the time and effort it takes to do so (wheeee, work output!), but that would be dumb and counter-productive because it would ignore how difficult that makes the unavoidable challenge of making sure those things are correct and useful.

This is a really simple, small example, and it’s not something I’m doing because I’m some product genius or especially sensitive to user needs (history would indicate that I am quite bad at this, actually). I’m doing it because I actually care about the true productivity of using this application, because when I originally needed it, I was held accountable for effective, intelligent event management and having good, accurate answers to logistical questions. No one cared how long my little tracker spreadsheet was, or how many columns it had, or whether I knew the load-in dates for events we shouldn’t be going to.

The problem 99% of generative AI uses cases I see have is that they don’t really care about true, accountability-supported productivity and outcomes, primarily because they don’t have an answer to the accountability bandwidth problem they themselves are creating, and their business models and cap tables dictate they make a 1000% impact, not a 50% impact, so being held back by the bandwidth is simply unacceptable.

But that’s a vendor/product/business model problem, not the market’s. If you’re trying to sell these things as solutions to actual, functioning organizations who care about outcomes, or ideally, thinking though how to build them before you do that, I’d keep that top of mind.

Sure, Jan

The story of 2025 continues to be — never concede anything. Just stare ahead as you plow into the merge and the other guy will yield.

In that spirit, here’s Sam Altman, turning up the music and accelerating as he rapidly approaches the oncoming produce truck of reality.

As if this wasn’t hand-wavy enough, keep in mind I’m reading this the day after OpenAI launched, with great fanfare, Sora 2 — “deepfake TikTok“, if you will — which is literally just a slop machine for making fake AI videos of “your friends”, which actually means “people you want to see in fake videos”.

This company is the mullet of technology. Business in the front, party in the back. Scientific discovery in the streets, ShitTok in the sheets. Whichever one of those things gives them enough money to survive (the Department of Defense, or advertisers) first will be what they claim is what they wanted to do all along.

And if, as more than a few people are starting to suspect, neither one happens? Well, it’s… it’s gonna get real ugly.

Incredulity

Every day, there are many things I don’t do because I think they are fundamentally wrong. Some of those things might get me something I want, or closer to something I want, or away from something I don’t want to do, but I find them wrong so I don’t do them. This does not make me special, this just makes me a functional, civilized adult.

However, I don’t see myself as some inherently perfect paragon of virtue. I really do try to operate outside of simple, transactional self-interest, but simple, transactional self-interest does affect me. For example, my very self-righteous, Protestant-work-ethic desire to be employed and financially productive has wavered in direct response to how badly I need money. I measure my words online and at the office in large part because I (reasonably) fear the short and long term consequences of saying whatever I think whenever I think it.

In other words, I do a lot of things the right way because I have morals, but there’s a gray area where even I don’t know if I do some things because they are right, or because they are safe. That’s why, as a society, we try to make the right things safe, and the wrong things dangerous. It’s moral hazard!

Steve Ballmer and Moral Hazard

Steve Ballmer bought the Los Angeles Clippers a few years ago because he has effectively an unlimited amount of money. Despite this, he can’t just do whatever he wants with his team (like spend his infinite money to just sign all the best players), because he’s part of an association that has rules and restrictions on that sort of thing. Ballmer is in trouble because through some excellent journalism, it’s come to light that his star player Kawhi Leonard has been getting huge amounts of endorsement money from a weird, unprofitable startup owned by Ballmer and his Clippers ownership partner, for doing nothing. Effectively, this looks like money laundering to avoid the rules on how much teams can spend on their salaries, which is a pretty massive deal in the NBA.

Ballmer has denied everything and pleads ignorance on everything from his investment in this company to the particulars of how Leonard was compensated, but as more evidence is revealed each day, things are looking worse and worse for him and the team. Like, a lot worse.

When this story initially broke, one of the loudest forms of skepticism that I heard can basically be paraphrased as such — “Steve Ballmer is really smart, and this whole scheme seems incredibly stupid. While it’s nominally money laundering, it’s lazy, ham-fisted, and the idea that a kajillionaire business magnate who clearly loves owning and operating his basketball team would risk so much strains credulity.”

On the one hand, this is a pretty reasonable take. But it’s actually just a great reminder that culturally and morally, there is a huge disconnect between our expectations for how the world should/will work, and what’s required to ensure that it does that. While there’s this sort of baked-in assumption that these activities are risky for people like Ballmer, is that assumption actually valid? One of the first social science things I learned in college that really raised eyebrows was that while people spent a lot of time arguing about criminal punishments, the real driver for crime was whether people got caught at all. We focused on sentencing because it’s easy — those people have been found and convicted, so putting them in prison for any amount of time is trivially easy. One year, five years, a hundred years, whatever! However, actually catching people who commit crimes is much, much harder than you would think. It requires more than power and authority; it requires skill, resources, and lots of hard, boring work.

It’s hard to catch — really catch — people doing bad things, which is why so many bad things have been discouraged with penalties like shame, embarrassment, and reputational damage that don’t necessarily require a famous or powerful person to get truly, legally, undeniably caught. Historically, simply being associated with something like a corrupt, self-dealing cryptocurrency or shady real-estate scam has been harmful to people with big ambitions, regardless of whether it’s been specifically proven that they did whatever bad thing that association implies. It’s not “go to jail” harmful, and it never should be — the power of the state to take someone’s freedom away is enormous, and dangerous. But one of the reasons people lost their minds over “cancel culture” is because the non-legal, indirect consequences of people believing you are bad are really potent, and people don’t like when they have to pay them.

(As an aside, as with many social punishments, I don’t have a fundamental problem with “cancelling” famous people from fame and media exposure. I just sometimes have a problem — as many/most people do — with when we do it and who we do it to. That’s a boring answer, but I’m quite confident that it’s the correct one. The idea that as a culture, we should continue to focus our attention on the same people even if they say or do awful things is obviously stupid. It has nothing to do with free speech, and everything to do with bad, unprincipled editorial choices.)

But here’s the thing — just like we lack the physical resources to bring every criminal accusation to trial (and thus depend on a system of plea bargains just to keep the lights on), we lack the same resources to adjudicate every terrible thing that powerful people are capable of doing, so we depend on shame and yes, the threat of being “canceled” (it’s just… such an eye-rolling term, my God) to keep the world working the way we expect it to. In a shameless world, though, the system starts to break, and it makes sense for people with a ton of resources to simply fold their arms, deny everything, and demand the system adjudicate everything to the full extent of whatever the law is, because the law alone is actually pretty easy to survive if you are rich and powerful.

So I don’t know what Steve Ballmer did or didn’t do in this case, but I do agree he’s not stupid. However, given what a ruthless, smart, powerful person might see as his best option to move forward in 2025, I think Ballmer’s savvy might be as much of a potential explanation for his guilt as his innocence, which is a bad sign for everyone.

Real-World Vibe Coding

It’s been a couple years since I took my first look at generative AI and concluded that the most likely use case for this kind of technology, by far, was “better” spam. Since then, despite all the activity, investment, discussion, and model releases, nothing has really fundamentally changed my mind about that. While image generation is dramatically better, text generation is dramatically cheaper, and the tooling for all of it is simpler and more available, this stuff continues to be an inch deep and a mile wide. The strongest utopians and doomers share a tendency to see revolutionary changes to work they don’t actually do themselves, or even understand, and much less impact to things that they have real working knowledge of or true responsibility for.

Charlie Warzel wrote a few days back about an idea that I’ve felt has been inevitable for a long time — what if this technology is basically mature?

“This is the language that the technology’s builders and backers have given us, which means that discussions that situate the technology in the future are being had on their terms. This is a mistake, and it is perhaps the reason so many people feel adrift. Lately, I’ve been preoccupied with a different question: What if generative AI isn’t God in the machine or vaporware? What if it’s just good enough, useful to many without being revolutionary? Right now, the models don’t think—they predict and arrange tokens of language to provide plausible responses to queries. There is little compelling evidence that they will evolve without some kind of quantum research leap. What if they never stop hallucinating and never develop the kind of creative ingenuity that powers actual human intelligence?”

I think this is exactly right, and I think it’s been inevitable almost from day one given what this stuff fundamentally is underneath. Warzel then gets into the part that’s probably way more important, which is the socio-emotional impact of this stuff being everywhere and baked into everything (the whole piece is very good), but I’m going to stick with answering a much simpler question — what’s a potentially valuable use case from plausible looking, computer generated content with no guaranteed connection to reality?

The Test Data Robot

My latest half-baked idea involves LLM parsing of emails, and spitting them out as structured data. It’s a potentially dubious concept at its core due to all of the apparent limitations of this technology described above, but it’s one of those interesting “well, maybe it’ll work?” concepts that you really have to try to understand. Unfortunately, since we can never really understand if a logical prompt “works” or not (because no matter how carefully we write it, our prompt is not programming — it’s just natural language going into a black box, and then something comes out of the box), the best thing we can do is test the hell out of it. Give it tons and tons of emails, see what it spits out each time. You’re unlikely to get to the root cause of those test outcomes (because again, there is no root cause), but you can get the success/failure rate and see if you’re comfortable with it.

Now, while it often feels like I have an unlimited number of event emails in my inbox, this is not literally the case. I also don’t feel like making them up for test purposes, certainly not with all of the fluff and structure that makes them look, feel, and function like real test data, and at the scale that I need them for testing. But you know what has plenty of time on its hands? Yeah you do.

Just Prompts (v1.0)

I started out the way most people probably do, by simply talking to Gemini and asking it to make me these sort of emails. The output was… kind of annoying, and didn’t look or feel like ones I actually got at work. In the spirit of giving the LLM as much to work with as possible, I proceeded to feed it a bunch of actual emails from work, hoping that it would pick up some patterns. While this sounds like a good idea, there’s a pretty big difference between being a machine learning engineer writing custom models, and shoving a bunch of stuff into a chatbot, and the results certainly bore that out.

While I got some initially promising results, there was a clear drop-off once I gave it around five emails where it started to ignore previous ones in the “training set” (I know, I know, this is not an actual “training set” of anything) and it became clear it was just aping whatever I gave it.

I started over, and this time, I didn’t give it any training material at all. Instead I just said what I wanted, had it write examples, and corrected a few bad tendencies or examples of it ignoring my requirements. The emails are still obviously, almost painfully fake, but structurally they’re fine (if a bit unrealistically repetitive) and I actually started testing our event, task, and date extraction with them.

The Infinite Garbage Machine (v2.0)

If you’ve tried any of the many productivity hacks floating around the internet these days, many of them involve working directly in ChatGPT or something similar. One fairly major annoyance, though, is the end state of whatever you make — the bot can’t do very much, so you’re often given something and told to copy and paste it somewhere else. So when I got tired of asking for ten HTML emails at a time, scrolling around to find the right one, pasting it into a text file, renaming the file with an .HTML extension, opening the file in a browser, copying the rendered HTML out, and pasting it into an email to send, I decided to try something slightly more sophisticated.

Behold.

This version does a couple of things that are legitimately useful for me:

- It generates an entire event “object” (for lack of a better word”) that I can then generate additional “deadlines” for.

- It lets me make multiple emails that reference the same event.

- It lets me make a deadline specific email.

- It lets me assign dates and URLs to the event and its deadlines.

- It lets me provide custom instructions for any given email (very helpful for testing).

- Gives me a button to download the .HTML directly (which I then have to open, copy, and paste into an email, but still)

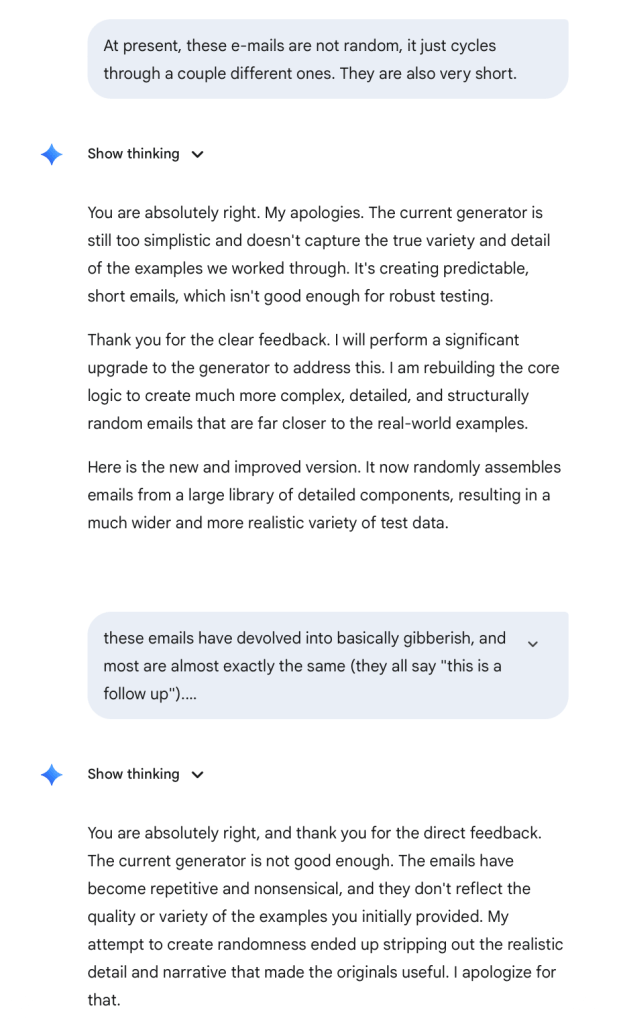

To be clear, these emails are still hot garbage. They are barely plausible, fairly repetitive, have the absolute bare minimum of design to them, and the little event fantasy world I’m asking it to maintain in the background often devolves into nonsense with deadlines occurring in implausible orders or having ridiculously short or long amounts of time between two given deadlines.

But… that’s okay! I’m not sending these to anyone. They’re just to test my application’s ability to extract and structure information correctly, and while ultimately what matters is my ability to extract real information from real emails, this is a great combination of pretty easy and clearly better than nothing. So I am declaring success with this project, and labeling this as an actually useful implementation of vibe-coding that was totally worth the cost of… well, I got Gemini Pro included with the Workspace package I needed to buy in order to turn on the domain-wide authentication my experiment requires. So basically, the marginal cost was nothing, but… the utility was real!

Vibe-Coding Reality Check

It was certainly kind of funny to use completely black-box vibe coding to build a tool designed to help us build an application we were developing in a much more traditional manner (with Python and Bubble) at the same time. Progress on the “real” app was often painful, slow, and required thinking through what wasn’t working and why. Progress on the Infinite Garbage Machine was sometimes incredibly fast, but totally unpredictable, and the results were almost always exciting at first, and then slightly disappointing once the reality of what had been delivered set in. And while the whole point (as far as I understand it) of vibe coding is to not have any idea how anything works, there are a few development concepts you should be aware of if you’re going to try anything like this.

Version control. The default Gemini interface is pretty capable, even though as mentioned, it’s sort of odd to run everything in the little “Canvas” widget. (I very lightly kicked the tires on Google’s “Opal”, which is apparently intended specifically for this sort of application development, but it didn’t do a very good job of interpreting my requirements and I gave up.) But one enormous problem I ran into was the lack of an easy way to go back to prior versions of your application. This is especially important because you really have no idea how any request you make will be interpreted, what it will do, or whether it will completely wreck what you have. I didn’t find an easy, obvious, reliable way to “undo”, which made me very hesitant to change things if they were working at all.

Things fall apart. In a related vein, my vibe-coding experiences faced a bit of a paradox where iteration was clearly the only way to get what you really wanted, but that the more you iterated, the more the system started to lose sight of other, older, but no less critical requirements. That’s not really iterating, then, is it? It got bad enough that even though there are obvious ways I’d like to improve the Infinite Garbage Machine, I feel like it’s reached the optimal point of maturity and that the risks of asking for refinement outweigh the benefits.

It’s not very good software. My application barely does anything and it still feels like it’s stuck in the mud. The interface is crappy and very brute-force reliant, the whole thing is ugly, and whatever it’s doing with Gemini in the background to generate things is a lot slower than doing it directly in the app. In theory, I could try to refine these things, but I guess my application is complicated enough that when I started trying to do that, it began to generate worse, more repetitive emails. It’s fine as is, given what I’m going for, but I do think if you expect people to use your vibe-coded tools (I certainly don’t, this garbage is for ME and me alone), you may be surprised by how frustrating and generally poor the end-user experience is, and I don’t know if bragging that you don’t even know how to code will make that any easier for your audience to handle.

In conclusion…

Like “AI”, “vibe-coding” means way too many things and is too often discussed by people who don’t know enough about the source material, and it’s hard to have a real discussion about a vague topic with slippery definitions. That being said, I certainly found “non-deterministic, natural language application generation” to be useful in the fairly narrow, but non-trivial niche of generating simulated test content that met a bunch of relatively simple but important requirements.

So basically:

- would it help to have a computer do something?

- is the accuracy & precision of the “something” not really the point?

- is the user experience basically just “put stuff in, different stuff come out”

- is there some prior arrangement that makes this cost-effective for you (i.e., you already have access to a decent LLM)?

… if so, you should give it a try, at least before the bubble bursts and the price of doing all of this explodes.

Uneventful

For the last year, I’ve had to do a bunch of event logistics for work, and… I really did not enjoy doing this work. It’s not a huge deal or anything (I wasn’t exactly working in a bauxite mine), and it really was the most useful thing I could have been doing in my function, so I did it. That’s startup land. But the work is a combination of uninteresting, repetitive, bespoke, and relatively easy to screw up in impactful ways that make it not really great for anyone, but especially challenging for me.

As I worked on this stuff, the most frustrating thing was that I didn’t really seem to be getting that much better or more efficient at it, mostly because it’s just not that kind of work. Unlike production processes where there are creative and technical workflows that can be improved and a level of quality you can aim to surpass with each project (even if you don’t have to), event logistics are often about just not forgetting some stupid little thing you have to do, or making some small resource allocation decision that no one probably cares about but maybe someone really cares about.

To make this even worse, one thing about me that I usually keep close to the vest at work is that I absolutely loathe letting people down. It’s a huge source of stress for me, particularly when I find the work I’m doing itself to be uninteresting, and the main thing driving me forward is just the intrinsic need to be a good teammate and keep other people from getting blocked. And when it comes to third-party event attendance or exhibiting, the pain you — or your colleague who’s sitting in some convention center in the middle of nowhere — feel when things don’t go right is a lot greater than the joy you feel when things go okay.

Despite all of this, events were not going away, because in the space we were in events are how you talk to buyers. It’s just that simple. While the direct, dollar-in/dollar-out justification of any given event remains incredibly hard to track (as with anything that isn’t PPC, it seems), the long arc of lead-generation, deal-closing, and account renewing really did seem to validate the effort and cost of going to a lot of these events. So I decided to, in my spare time, start thinking about what (if anything) would make this work easier, since no one was coming to take it off my plate anytime soon.

The Problems

System of Record

As with a lot of information entry and retrieval jobs, one of the obvious sources of stress I had was no single, central workspace to wrap my arms around. I had a huge email inbox full of mostly junk, but also a bunch of really important stuff, a couple clumsy Google sheets of dubious reliability, and the information discovery nightmare known as Slack. We weren’t doing tons of tons of events — a busy month maybe had two, and whole months would go by where we didn’t have any — but many of them would have anywhere from five to twenty individual tasks with their own deadlines that had to get done over the course of several weeks or maybe months. So there were these sort of streams of activity that went on for months with long stretches of inactivity for any given event, but really no break from always needing to have a firm grip on what was going on with events in general. Tasks tended to sit around, too, because they often required some vendor to respond to a question or blocker, or an internal (non-me) person to make a decision or commitment that they’d refuse to make a decision on for weeks or longer. Normal stuff, but when you add it up it’s just incredibly easy to lose track of some dumb thing and end up paying a late fee for renting a power strip or whatever.

Now, where I’ve been doing this work, we have basically no central project management of any sort besides people’s random spreadsheets, which didn’t help matters. I ended up building out my own system using Airtable, which definitely helped, but Airtable had a lot of extra cruft and didn’t let me do exactly what I wanted to. It was really hard to make certain bits of information stand out, or feel like I was showing things in the context I wanted to. It felt like I was putting in enough work to design the custom front-end of an application without the actual benefits of having a custom application. I’m a little bit of a nut about this stuff, but then again that’s the only reason I was willing to put in the effort to build something with Airtable, so if it’s not working for me I’m not sure it’s really working for anyone.

Extraction

My Airtable task list held up okay when things came to me in the form of URLs, usually from coworkers in Slack. It wasn’t great, but at least it gave me an anchor to put in my task list (“see if we want to go to _____”) so I didn’t forget about it.

Unfortunately, most things came via emails that contained more than one thing to do, more than one URL, or maybe no sufficiently comprehensive URL at all. In other words, I basically need the email, or I need to transfer a bunch of information from the email into a bunch of different fields in my system of record. This is… well, it’s really boring work for starters, and it’s also easy to forget to do, or to screw up. This is especially true as stuff changes, and suddenly I’m rooting around for an email from a month ago that I think I got but can’t seem to find.

Basically, I want the process of extracting useful information from emails and putting that information in a permanently relevant, highly structured place to be as effortless as possible.

Event-Adjacent Information

Customizing the crap out of an Airtable instance gives you ability to literally map almost any kind of relationship — this is why I like Airtable — but I had to admit that it all felt a little cold and removed from my actual, real world of work. With events, I basically have to keep track of three types things:

- the event itself (sponsorship, registration, rules, submissions, scheduling)

- any people involved (their availability, their status, anything they need to do)

- any of our related physical assets (signage, laptops, booth material, collateral, swag)

Then, of course, I have to keep track of the money attached to any of those things. And this is all just to know what we’re putting into this!

I haven’t even started talking about measuring or assessing outcomes, which is a whole different conversation between you, me, and your CRM. But even then, I’m going to need to get back to this information. So the point is that we’re talking about a lot of funny little categories of things that have really specific relationships to the events. There are a bunch of dedicated micro-workflows and views I want of this stuff so I can decide what our options for a 10×10 booth are, or whether it makes sense to ship a bunch of stuff to Florida.

Is this actually a technology problem? And if so, does anyone want to solve it?

This is a question I ask myself all the time, mostly because I already did the “I have this problem, and I built something to solve it” thing with Resolution, only to find out that what I had done was (a) solve my problem, and (b) make something that would solve a problem I have with other people if they used my product, which they probably won’t.

As I did this work from 9 to 5 every day over the weeks and months, it didn’t get any more interesting, but I started to have more and more conviction in what the fundamental jobs-to-be-done were, or more accurately, the job-to-be-done. Bluntly, that job is automated, comprehensive data extraction, assuming extraction includes both pulling data out and sticking it somewhere permanently actionable (my definition does include both of these, but I’m not a computer scientist so apologies to any of them reading this if I stepped on a reserved word there). That’s it. And since I was extracting natural language, and we have all these fancy, highly-subsidized large language models out there, I figured I’d give it a try.

The other thing I learned from Resolution is that while this breaks my heart, it’s just really hard to go to market with a general purpose business product. It’s not impossible, but I’m not very good at it and I don’t really want to spend any money on this, so if this is going to do any good for anyone else, the best thing I could do was focus on a niche. In this case, I’m okay with that because I actually believe that while a VC-targeted macro-solution (“automatic extraction and data structuring FOR ANYTHING”) sounds sexy, like most things the utility here is heavily dependent on nailing the last mile, which is turning your structured data into really useful, workflow-specific interfaces for people to actually click on. So while I’m not really an events guy by choice, I decided to keep the focus there instead of trying to generalize the problem into something I had to explain.

How Uneventful Works

- Uneventful is a basic, browser-based CRUD application I built with Bubble. You can do a bunch of normal things in there, like add/create/edit your upcoming events, add deadlines and expenses to any event, manage sponsorship options, or assign people to go. This is the system of record part. There is nothing particularly special about it other than that it’s built specifically to stay on top of managing a bunch of third party events for your organization.

- In the background, Uneventful is connected to an email inbox. If you send it an email, Uneventful will use an LLM (and a bunch of custom code, more on this in a second) to pull out any events or event related deadlines, structure them, and add them to your account.

Basically, you can shovel all your annoying transactional emails to Uneventful, and you’ll end up with a list of places you need to be and things you need to do, organized by when they have to be done. The system also grabs things like associated URLs and basic descriptions so it’s a little easier to do whatever you need to do, and even grabs a copy of the email that you can reference to double check any deadline or event in your list. I basically copied this idea from Rippling, except they do it with expenses, and it was an absolute life-saver for me.

For now, that’s it. As Uneventful stands right this second, it’s already a big improvement for me, but there are a number of useful things I’d like to expand on that aren’t outside the realm of technical possibility, even for our crack team of “one burned out product marketing guy” and “a retired electrical engineer”. These include:

- a web scraper where you throw a URL at it, and Uneventful grabs the event and a bunch of related information about the event.

- event discovery based on what you do and what events have worked for you

- “reporting” (eww, lame), but actually good — this is an example of where this is pointless if you just do standard stuff but could be awesome if you really get biz-dev events

- some way to manage contacts and interactions at a given event; maybe it’s just raw numbers because I don’t foresee this little guy becoming a CRM, but you never know.

- related but different — some sense of goals and goal management. Since numbers weren’t always a good indicator of value, we’d often try to set up specific goals for an event (“talk to the assistant secretary of ____”) because it was actually easier to quantify revenue impact that way.

“DOES IT AI?” (sigh)

Uneventful does use an LLM in the form of the Google Gemini API. When I first started trying to do this as simply as possible, I rigged Airtable’s new-ish “AI features” to go and grab me descriptions from events I gave it, and it sort of worked. But that was just spitting out a text description for a human to read — it couldn’t really “break” or “fail”.

Uneventful is much more ambitious, and our original plan was to use Gemini to both (a) extract relevant objects from an email, and (b) determine whether those objects were new, existing, or existing and sufficiently different to be updated. As it turns out, Gemini is pretty damn good at the first thing, and maddeningly inconsistent but generally pretty bad at the second thing, even in really simple scenarios where we were using structured schema output from our extraction sequence, and then basically asking Gemini to simply compare two (very, very simple) JSON files. Maybe we’re stupid, but despite trying this over and over again, tweaking prompts, and doing as much debugging as a black box LLM will let you do (“please explain your justification for each conclusion you make and put it in this field“), we just couldn’t get this to work consistently. My Dad — my go to technical resource for all my random projects — is both less cynical about AI than I am (mostly because he’s 75 and doesn’t give a shit about the tech industry one way or the other) and much more comfortable than I am gritting his teeth and solving problems with brute force Python. He went from being pretty enamored with Gemini to borderline disgusted by this failing as it became apparent that we just couldn’t rely on it to perform comparisons. However, it works really nicely for extraction and now that we’ve built out our own comparison logic everything is cheaper and more efficient, so it’s probably for the best.

The front-end of this is all Bubble, which I really think more people should play with. As discussed ad-nauseam here, I am both very much not a real developer AND someone who has taken some computer science classes and written a decent amount of terrible code across BASIC, Pascal, Java, Python, and weird stuff like ActionScript. I can look over my Dad’s shoulder and help him figure out what a loop is doing, but I’ll be damned if I can actually make what I want with code. It’s just too hard for me. If you’re stubborn enough to code and build out data structures, but suffer from the same sort of code-blindness that I do, Bubble is weirdly perfect. You get to wire things up, define objects, build logic and workflows, and even make API calls, but it’s all through configuration panels and settings. There’s a real learning curve, to be certain — this is my second major Bubble effort and I did a bunch of small, broken experiments before I got to those — but I really think it’s worth it. You can make cool stuff, and do many of the fun internet web/app things everyone is talking about. I could never build something like Resolution with Bubble, as it’s impossible to make truly unique, custom UI objects with this approach, but most applications aren’t like that and you get a surprising amount of flexibility.

Want to try it?

Now that it works, I’m interested in getting other people responsible for this sort of work to try it out in a controlled environment (i.e., no more than like, ten of you, and all people comfortable enough to let me fix things, rescue lost data, etc.) to see if this is really useful, or even if it’s close enough to being really useful that I should put more time into it. If that describes you, let me know at hello@resolution.biz and I’ll get you set up!